This is the second in a series of posts, each one about an island we’re visiting while on our grand tour of French Polynesia. (The first post was about Mo’orea.)

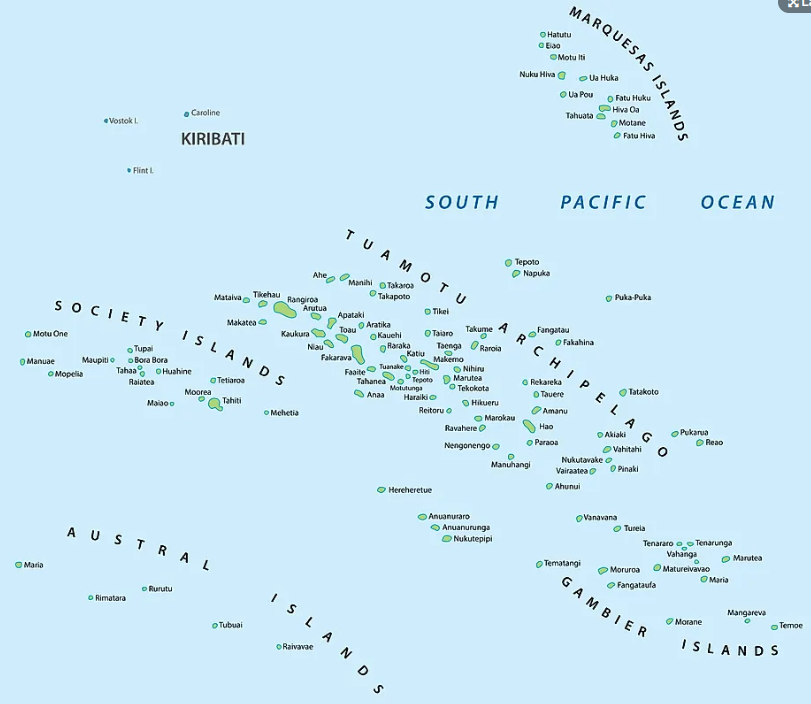

Rangiroa is an atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago, which is the middle, and largest, group of islands in French Polynesia. In the map below, it’s to the right of the “S” in “SOCIETY” and a little to the left of, and below, the “T” in “TUAMOTU”. While Mo’orea doesn’t have a whole lot of options for things to do, I think it’s safe to say that Rangiroa is even sleepier. It’s the largest atoll in French Polynesia and the second largest in the world – about 46 miles from end-to-end inside the lagoon. But the motus (islands) that make up the big oval around the lagoon are very narrow, very flat, and many of them are quite rocky (ancient coral reef), so not a lot grows on them. Except coconuts.

The first one we were on during our eleven day stay (the name of which I never was able to determine) had more coconut trees per square kilogram (or maybe square kilolitre? I never have understood the kilometric system) than anywhere we’ve ever been. (Except our backyard, of course.) And where you have a lot of coconut trees, you have a lot of… can you guess? No, not coconuts, numbskull – crabs! Big gray land crabs that live in holes the size of my left foot (ask me how I know this), and much smaller hermit crabs that live in seashells, and that make a really sad “crunch” sound when you accidentally step on them on your way to, well, anywhere.

There were a lot of coconuts, too – that’s what the crabs eat when they can get it. (The rest of the time, they seem to eat dirt, which may account for the really unhappy look on their faces.) So many that they’re in piles all over the island (coconuts, not crabs), waiting to be cracked open for the water and meat, or already harvested and waiting to be burned to help ward off the mosquitoes, or just lying there sprouting into – what else? – MORE coconut trees!

But Air Tahiti doesn’t have 32 flights a day to Rangiroa for the coconuts! No, only half the people come for the coconuts – a huge percentage of the flights are people arriving to buy black pearls, which are farmed / cultivated on Rangiroa, and sold in the pearl farm gift shop for 60 – 110% more than you can find them on just about any other island in French Polynesia.

The pearl farming thing is incredibly interesting. In a nutshell (or oyster shell), a mature oyster is gently pried open just enough for a technician to do some basic surgery inside. A slit is made into a part of the body of the oyster that they apparently don’t need, and into it is inserted a small – 6mm – sphere of Mississippi River clam shell (yes, really), along with a piece of the “mantile” from a donor oyster. (It’s on their driver’s license, so the technicians know which ones to use as donors.) The mantile is the tissue that normally generates the oyster’s shell, which is commonly known as mother of pearl. When placed inside the pocket with the sphere of clam shell, this piece of mantile grows and slowly covers the sphere with the same material that makes up the oyster’s shell. 18 months later, after receiving a bath each month (seriously), the oyster is gently pried open again (think gynecological exam, ladies), and the pearl is removed. At the same time, another sphere, this one the same size as the pearl which was removed, is placed back in the pocket, and the process starts over again, to make a bigger pearl. An oyster in French Polynesia can produce four pearls in its lifetime. After the fourth one, they get to retire. And by “retire”, I mean, they get a quick tour of the kitchen – wink wink, nudge nudge.

The process was invented over a period of 35 years, back in the 1800’s, by a Japanese man referred to as Mr. Makimoto. His goal was to produce perfectly round pearls, which were very rare up to that point. Now, about one in ten cultured pearls is round. Some are not quite round (they don’t roll straight on a glass tabletop), some are more oval or teardrop shape, and some are “none of the above”, due to some mishap in the process, such as a piece of sand getting inside the pocket before it heals shut.

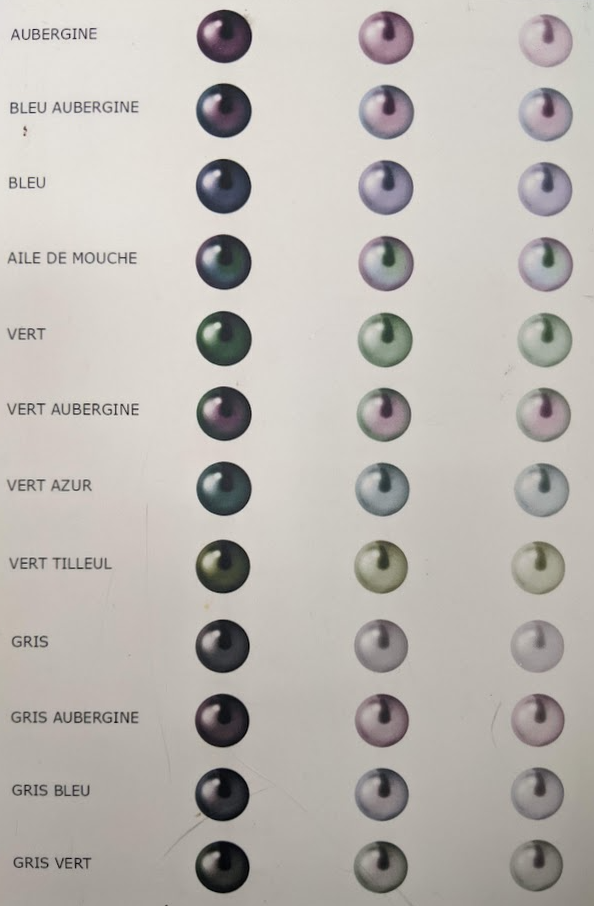

The pearls of French Polynesia are referred to as black pearls, but they’re really mostly some shade of gray, ranging from almost silver to almost black. But some oysters throw in a little color into their work, so the pearls can appear greenish, bluish, pinkish, or purplish – and those are the most expensive-ish. A large (14 – 16mm) round pearl with great color(s), superb luster, and no imperfections sells for something in the neighborhood of $16,000. Obviously, Fran and I are not in that neighborhood, or school district, county, or state. The few pearls we’ll be bringing back are referred to here as “tourist bait”. You can buy them by the handful for $13 each, so you can take them home and make them into your own jewelry (which I swear I’m going to do, as soon as I learn how to make jewelry!).

But the REAL reason to visit Rangiroa is not coconuts, and it’s not pearls – it’s scuba diving. (And now I’m being totally serious.) The ocean flows into and out of the lagoon with each tide change, primarily through two large gaps between motus, called passes. One pass is only for boat traffic, the other mainly for scuba diving. And the scuba diving is spectacular! We dove five times, and the first three were three of the best dives Fran and I have ever done. Each dive starts on the outside of the pass, in open water where the island drops off into the depths. The initial objective of every dive is dolphins – there are a group of them that hang out in that area – and they are friendly! We had two or more pay us a visit on three or four of our five dives, with at least one of them each time being very interactive with the divemaster. On one dive, as Fran was filming that interaction, another one swam up behind her so close that she just reached out her hand to stroke it as it swam by.

After the dolphins, the dive moves into shallower water (50 feet or so), on the steep slope of the reef. The coral is abundant and very healthy, and the fish are everywhere, all the time. Every size, shape, color, pattern, texture, and behavior you can imagine from a fish, and it’s happening right before your eyes. Or your camera lens, which presents an interesting problem – which fish to shoot? The spectacular Moorish Idol, with its striking white, yellow, and black colors, funny snout with the pattern, and long, wavy filament-like top fin? Or maybe the very shy Flame Angelfish – bright orange with brilliant blue stripes and accents on fins and tail? Possibly the pair of (fill in the blank – there are about a dozen types) Butterfly Fish flitting tantalizingly near (but often just out of camera range). And all of that can – and often does – happen within the span of 30 seconds.

After 15 – 25 minutes on the slope, it’s time to actually enter the pass. (If there’s an incoming tide – if it’s outgoing, the whole dive happens out on the slope.) The current starts to carry you, slowly at first, and your inclination is to resist it, to stay in one place for a bit. But very soon, you pick up speed, until you feel like you’re on the observation deck on a train, just looking out at the gorgeous scenery as you pass by. The scenery will certainly include the common sharks (gray reef, white tip, and black tip), possibly spotted eagle rays, manta rays, the big sharks (tiger and hammerhead), moray eels, the giant Napolean Wrasse, and a continuation of the assortment of fish that started on the slope. Eventually, the divemaster gives the signal that it’s time to end the dive, and you begin to sob.

Our first dive included good friends Whitey and Max, (more about them in a minute), who are no strangers to great diving. When we all surfaced at the end, every one of us exclaimed something like “WOW!” or “Oh my god!” or “That was fantastic!”. We dove with them twice more, both times with similar results – lots of grey reef sharks, a manta ray(!), dolphins, and all the other usual suspects. By the way, we dove our best three dives with Y AKA Plongee (“plongee” means “diving” in French), a small husband-and-wife operation that we loved. There are several other dive operations, and Fran and I did dive with one other later, but we liked Y AKA the best.

Coincidentally, Whitey and Max (John and Maxine White) are on their round-the-world sailing adventure, too, about a month ahead of Liz and Paul, the couple we started this trip with (Panama to Galapagos). Through no planning, but excellent luck, we were on Rangiroa at the same time Max and Whitey were, so we got to dive with them. And it looks like we’ll cross paths with them again in a few weeks, when we’re all on Ra’iatea at the same time.

Now you now more about Rangiroa than you probably wanted to know, and more than I intended to tell you. The only thing left for me to do now is point you to our Google Photos Library, cleverly titled “Rangiroa”: click here to see it.

I’m worried that this dive heaven might tarnish all your future dives. As in “That was a great dive but… (thinking about French Polynesia)”

When you have a chance come back to Indiana. You can dive in mud bottom farm ponds here. On a really clear day you might see a tire or a carp.

We’ll be back in Indiana one of these days, but not with the dive gear! I’ve actually done a handful of dives in quarries there – 3 or 4 bluegills, or even a largemouth bass are not going to compare to dolphins, sharks, and endless butterfly fish.

Absolutely amazing pictures and videos! So many eels and the video of you floating along with the current was cool.

Thanks, Jeff! Glad you liked it. Hope all is well with you and Julie.